The historic Dew Drop Inn comes back to life after a stunning renovation

In recent years, a vintage sign hanging on the front of the Dew Drop Inn was one of the few reminders of the legendary hotel and music venue’s mid-century heyday. Its halls once echoed with the sounds of musical greats from Etta James to James Brown, but the club had fallen silent, and its facade on LaSalle Street sat covered in layers of fading plywood, peeling siding and deteriorating Permastone.

Local developer Curtis Doucette Jr. purchased the vacant site in 2021 — after previous developers’ revitalization attempts had fallen through — with hopes of reviving the Dew Drop as a music venue and hotel. He was immediately drawn to its storied history and the role it played in the evolution of music.

“This is the first time I really fell in love with a building,” Doucette said, “and there was a lot of learning for me.”

Doucette is a New Orleans native who has worked for the past 20 years to develop new housing and renovate residential buildings throughout the city with his company Iris Development. The Dew Drop Inn was a personal passion project, marking his first venture into the hospitality sector as well as his first project utilizing historic rehabilitation tax credits. The site qualified for the Louisiana Commercial Tax Credit, commonly called the state historic tax credit, but the building needed to be listed in the National Register of Historic Places to qualify for the federal historic rehabilitation tax credit. Doucette worked with Gabrielle Begue of MacRostie Historic Advisors to nominate the building to the National Register and manage the tax credit process that catalyzed the building’s rebirth.

In 2021, the team began to peel back the building’s faded exterior layers to ensure that enough historic fabric was intact to qualify. Original details emerged from beneath the more modern layers, exposing an original arched entrance flanked by lunette windows, a mission-style parapet and exterior walls covered in faded red-orange paint.

“It was a moment where I wish we had TV cameras there, because that was the moment where we realized we had a project,” Doucette said.

After an extensive rehabilitation project, the restored façade and signage at the historic Dew Drop Inn once again light up LaSalle Street in Central City. Photo by Charles E. Leche.

The building is comprised of two early-20th-century residences that club owner Frank Painia joined together in the 1940s, elevating one of the former homes to create a commercial space below. Photograph courtesy of Tulane University, William Ransom Hogan Archive of New Orleans Jazz.

Audiences at the Dew Drop Inn watch a performance by vaudeville entertainer Lollypop Jones in 1952. Photograph courtesy of Tulane University, William Ransom Hogan Archive of New Orleans Jazz.

Audiences at the Dew Drop Inn watch a performance by vaudeville entertainer Lollypop Jones in 1952. Photograph courtesy of Tulane University, William Ransom Hogan Archive of New Orleans Jazz.

Patsy Vidalia (center) emcees a dance contest for “female impersonators” in 1954. Also on stage is singer Bobby Marchan (left) who often performed as a female impersonator. Photograph courtesy of Tulane University, William Ransom Hogan Archive of New Orleans Jazz.

Cultural significance

The site’s nomination to the National Register of Historic Places was approved by the National Park Service in 2022. Instead of architectural merit, it was nominated for its cultural significance as the premier venue for Black musicians in segregated New Orleans during the mid-20th century.

“The Dew Drop is the only venue of its kind to survive from the period of significance (1945-1965), and it has a very high level of historic significance,” Begue said.

The nomination also details the history of Frank Painia, who founded the Dew Drop as a family business. Painia had worked as a barber on LaSalle Street in the 1930s, until his shop was demolished by the federal government to build the Magnolia Street Housing Project — the country’s first federal housing complex for African Americans. In 1939, Painia moved across the street to 2836 LaSalle to rent a new space for a barbershop and a bar called the Dew Drop Inn. As business grew, Painia purchased the building next door and expanded his operation to include a hotel, restaurant and night club, which became an instant success.

“I see this as a story of Black economic resilience,” Doucette said. “We didn’t have a society that was designed for someone like Frank to thrive, but he did.”

Painia’s business became a popular stop on what was called the Chitlin’ Circuit, a network of venues that welcomed Black performers during Jim Crow-era segregation. The site was also listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book, a mid-20th century travel guide which published information on safe places for Black travelers to stay, dine and visit during segregation.

The club flourished throughout the 1950s and 1960s, attracting local talent — including Allen Toussaint, Deacon John and Irma Thomas — as well as internationally famous stars. Etta James, Ray Charles, Ike and Tuna Turner, James Brown and Otis Redding are only a handful of the superstars who performed on the Dew Drop’s stage.

“Meet those fine gals, your buddies and your pals, down in New Orleans on a street they call LaSalle,” penned local artist Esquerita in a song about the venue. “Down at the Dew Drop Inn, you meet all your fine friends, baby do drop in, I’ll meet you at the Dew Drop Inn.” The song was recorded by Little Richard in 1970, who also frequented the Dew Drop and gained many of his musical and stylistic influences from Esquerita.

In addition to its influence on musical history, the Dew Drop Inn was a trailblazer for LGBTQ+ history. One of the club’s most beloved figures was the vivacious Patsy Vidalia, a “female impersonator” — as described at the time — who worked as the Dew Drop’s star emcee from the 1950s to the 1970s. Apart from hosting musical acts and drag shows, Vidalia held the New Orleans Gay Ball at the club every Halloween, which became one of the club’s most popular annual events. Long before the Stonewall Riots of 1969, the club served as a haven for those whose orientation or gender identity clashed with the rigid social norms of mid-century America, setting the stage for the Gay Liberation Movement in the following decades.

“All are welcome, that’s part of our history,” Doucette said. Painia “went to jail to prove that everybody was welcome.”

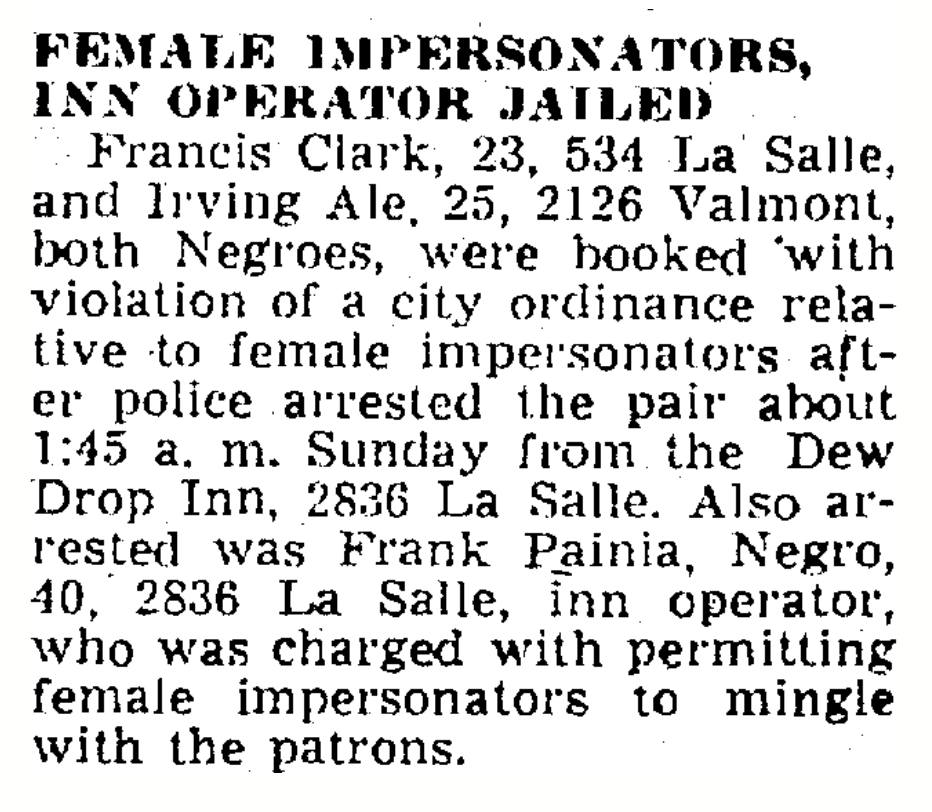

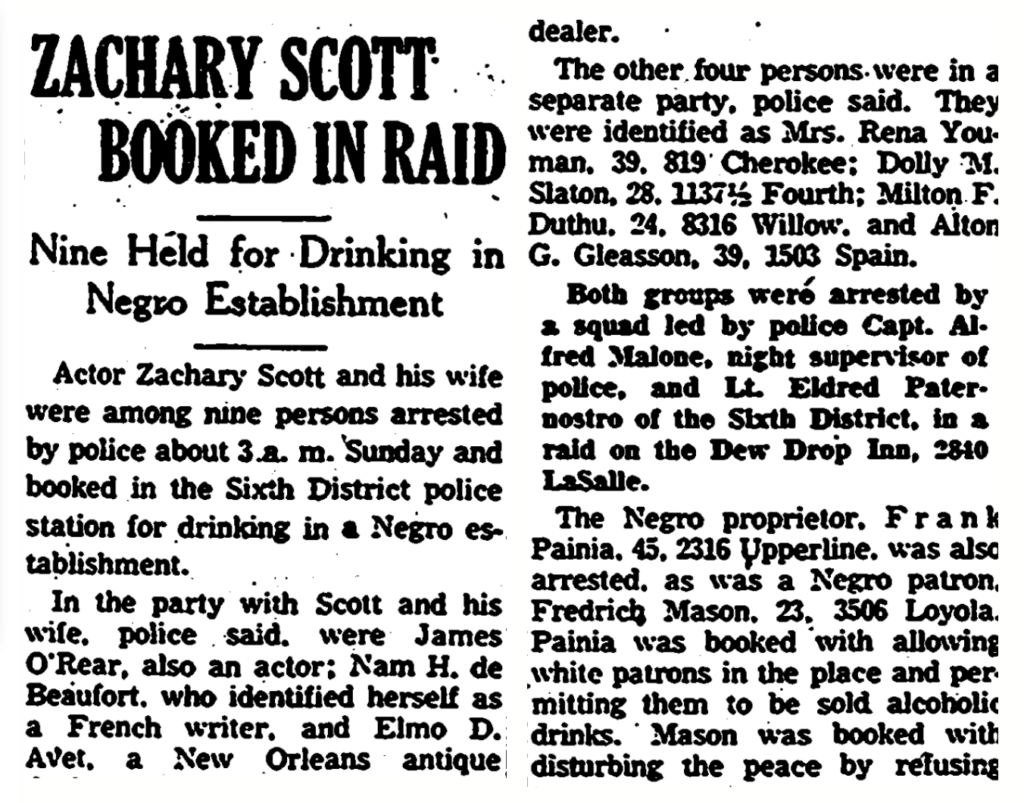

The Dew Drop’s welcoming attitudes towards race and identity attracted scrutiny from law enforcement, and police raids at the club were common. In a 1947 raid, Painia and Patsy Vidalia (reported as legal name Irving Ale in newspapers) were both arrested for “permitting female impersonators to mingle with the patrons,” The Times-Picayune reported. In another highly publicized incident in 1952, screen actor Zachary Scott and other patrons were arrested for “drinking in a Negro establishment,” the paper reported, and Painia was arrested for violating segregation laws by allowing white patrons in the space.

Painia worked with lawyers Ernest “Dutch” Morial and A.P. Tureaud to sue the City of New Orleans and challenge unjust segregation laws. They successfully gained an injunction to end police raids, but the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed before the case was finalized. As Black patrons had more entertainment options after the act’s passing, audiences at the Dew Drop and other establishments formerly reserved for Black patrons began to dwindle.

Live performances at the Dew Drop ended in 1970, and Painia passed away in 1972. The Painia family continued to operate the hotel portion of the business until Hurricane Katrina flooded the building, and the site remained vacant until Doucette purchased it from Painia’s grandson Kenneth Jackson in 2021.

The Times Picayune, June 30, 1947.

The Times Picayune, November 17, 1952.

Bringing back a landmark

After the building purchase, Doucette embarked on a multi-year renovation to revive the storied landmark into a hotel, music venue, bar and restaurant that will carry the Dew Drop’s legendary past into the future. Doucette worked with Studio Kiro as the project’s architects and interior designers. Teams with Ryan Gootee General Contractors worked to restore the historic structure and build out the new space.

The building is comprised of two early-20th-century wood-frame residences that Painia joined together in the 1940s, elevating one of the former homes to create a commercial space below. Previously hidden, the exterior walls and wood sash windows of the former residences are now visible and serve as a lightwell to the public area below.

On the building’s first floor, a versatile space doubles as both a restaurant and a bar. The restaurant will serve breakfast and lunch during the day, while the bar takes over during evening performances, serving drinks to patrons alongside the newly installed stage for musical acts. Furnishings throughout the public areas and hotel rooms evoke a modern take on mid-century design, apropos of the club’s heyday.

After a restoration, one of the original barber chairs shines like new in the former barber shop. That space, from which Painia launched the Dew Drop, will feature interactive public exhibits to educate visitors about the site’s storied history. An oral history listening station will showcase interviews from Tulane University Special Collections with musicians who once performed at the venue.

The building’s corridors retain all the original hotel doors, but its formerly 29 rooms have been joined together to create 17 larger rooms to meet the needs of modern-day travelers. Most are named after those who breathed life into the Dew Drop during its prime. The Irma Thomas, Earl King and Deacon John Rooms, for example, all contain exhibits designed by Civic Studio describing the artists’ lives and their connection to the Dew Drop. The Rights Room interprets A.P. Tureaud and “Dutch” Morial’s efforts to end segregation and police raids at the venue. Roosevelt’s Room interprets the story of Roosevelt Randolph, the hotel’s caretaker who looked after the building long after musical performances stopped.

On the building’s first floor, a versatile space doubles as both a restaurant and a bar. The restaurant will serve breakfast and lunch during the day, while the bar takes over during evening performances, serving drinks to patrons alongside the new stage for musical acts. Photo by Charles E. Leche.

The hotel rooms are named after performers and other individuals who breathed life into the Dew Drop during its prime. Each room contains unique exhibits designed by Civic Studio that describe the namesake artist’s life and their connection to the venue. Photo by Charles E. Leche.

Furnishings throughout public areas and hotel rooms evoke a modern take on mid-century design, apropos of the club’s heyday. Photo by Charles E. Leche.

Two suites overlook the main stage through folding doors that can be opened or closed during performances; one is named after Frank Painia’s Groove Room (the Dew Drop’s second venue, formerly located behind the hotel and demolished in the 1990s) and one named the Nitecap Room, after another nearby club that was owned by Doucette’s family.

“We’re continuing the legacy of this place as a family-owned business,” Doucette said. “My aunt will be doing the food, and my son has done a lot of the artwork as well as the signage.”

The nearly $11 million project — $6 million of which were construction costs — was made possible with state and federal historic rehabilitation tax credits. The site also received a $50,000 grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund to support historic exhibits. Other financing came from Community Development Block Grant funding, financing from the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority at a below-market interest rate and additional equity from New Market Tax Credits. Doucette put his own personal investment as equity into the project, as well as many of his friends, family and other investors — including the Painia family, who will retain a portion of ownership in the project, Doucette said.

The Dew Drop’s hotel rooms have started accepting reservations. The bar, restaurant and music venue are scheduled to follow suit soon. Social media users can keep an eye on @dewdropinnnola on Instagram for updates on when the music will return to the Dew Drop’s stage.

As the project wraps up, Doucette and another investor have also purchased the abandoned building next door to the Dew Drop, with plans to create additional hotel rooms that will highlight the history of Central City and other neighborhood figures.

“This is already a neighborhood that is culturally rich,” Doucette said. “What we would like to do is become an anchor for cultural expression.”